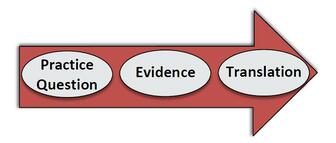

JOHN HOPKINS NURSING EBP Searching for evidence PHASE

The John Hopkins Nursing Evidence Based Practice Model includes five steps in its searching for evidence phase. They are listed below.

- Step 7: Conduct internal and external search for evidence

- Step 8: Appraise the level and quality of each piece of evidence

- Step 9: Summarize the individual evidence

- Step 10: Synthesize overall strength and quality of evidence

- Step 11: Develop recommendations for change based on evidence synthesis

- Strong, compelling evidence, consistent results

- Good evidence, consistent results

- Good evidence, conflicting results

- Insufficient or absent evidence

Step 7: Conduct internal and external search for evidence

Conducting an effective SEARCH For Evidence

- Identify your topic – use your PICO.

- Identify the resources to search.

- Assemble and sort your search terms.

- Run and refine your search.

- Record and evaluate your findings.

- Critically evaluate the information.

Source: "EBP Boot Camp Searching for Evidence" by Julie Nanavati and Carrie Price, Welch Medical Library is licensed under CC BY 4.0

1. Identify your topic

To begin constructing your search strategy to find the evidence, you must first identify your the key terms related to your topic. The best way to accomplish this is by examining the PICO question you developed during the practice question phase.

2. Identify the resources to search: Databases

To find the evidence that answers your clinical question, you'll need to use a database. Here, at Ellis, we have access to several nursing-specific databases that will help you to locate abstracts or full-text articles related to your subject.

**A note: The librarian does not recommend using Google as a starting place for your literature searches. The huge amount of unrelated and low-quality results can be overwhelming for a novice searcher. If using the below databases does not produce adequate results, please contact the librarian at [email protected] or 518.243.4381 for assistance.

CINAHL

STEP-BY-STEP INSTRUCTIONS FOR USING CINAHL

**You can download these instructions as a PDF by clicking the arrow in the upper right corner.

|

What should you do if you find an abstract in CINAHL, but the full-text is not available? |

See the below instructions for using the TDNet Search Box on the ellismedlibrary.org homepage!

You can also email your request to [email protected]. |

Retrieving & Ordering Full-Text: TD Net Search box

***To reach the TDNet portal from home, you will need to create a login from an Ellis computer first, or login via Citrix. For help, please contact the librarian at [email protected] .

PUBMED

STEP-BY-STEP INSTRUCTIONS FOR PUBMED

**You can download these instructions as a PDF by clicking the arrow in the upper right corner.

PUBMED TUTORIALS

PubMed offers a number of advanced services that can make searching for the answer to your clinical question easier.

PUBMED CLINICAL QUERIES

PubMed has a built in clinical query search that allows you to search for articles based on the type of clinical question you are asking, such as therapy, prognosis, etc. Watch the above video from the Health Sciences and Human Service Library at the University of Maryland to learn how PubMed Clinical Queries work.

MESH

MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) is the National Library of Medicine's controlled vocabulary thesaurus, used for indexing articles for the MEDLINE®/PubMED® database. Each article citation is associated with a set of MeSH terms that describe the content of the citation. If you can search using MeSH entry terms instead of keyword searching you can focus your search and find more relevant citations.

- To search PubMed using MeSH terminology, click HERE

BOOLEAN OPERATORS

- Booleans are operators (like + and – in math) that were created specially for searching.

- There are 3 main Booleans: AND, OR, NOT

- AND tells a search engine to return results that include both terms (example: nursing AND communication)

- OR returns results that include either search term, and it is useful for searching words that are closely associated (example: doctor OR physician)

- NOT returns results that exclude a term from your search. (example: apple NOT iPhone)

CONSTRUCTING BOOLEAN PHRASE EXAMPLE

Let's say you wanted to conduct a search for articles about nurse-to-nurse shift reports and how they relate to patient safety. And let's say you know shift reports are also called hand offs.

For this search, your Boolean phrase will be:

(shift report OR hand off) AND nurse AND patient safety

Let’s look at why:

For this search, your Boolean phrase will be:

(shift report OR hand off) AND nurse AND patient safety

Let’s look at why:

- We used OR because we want to return results with either shift report or hand off because those terms mean the same thing, and authors may have used one of these terms or the other, but probably not both.

- We used parentheses ( ) to separate the OR statement from the rest of the Boolean phrase, otherwise we’d be searching for the term shift report by itself– or hand off + nurse + patient safety.

- We used AND to include terms that must appear in our results.

For more in depth training on MeSH and Boolean searching, click HERE

Step 8: Appraise the level and quality of each piece of evidence

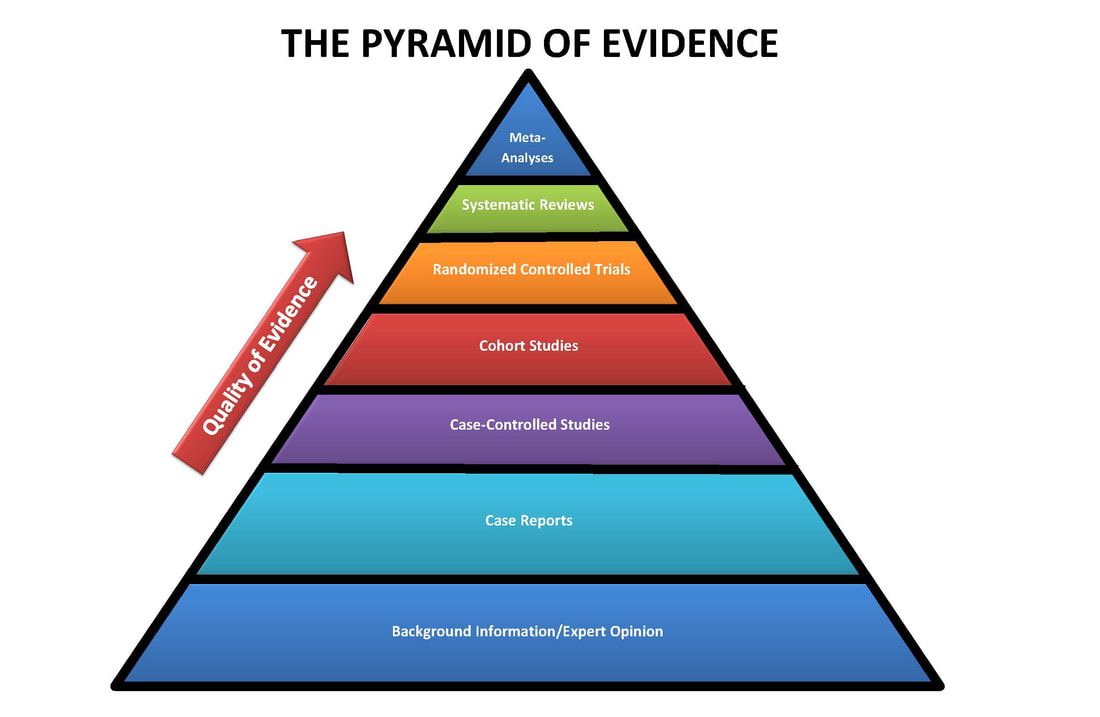

LEVELS OF EVIDENCE

When searching for information, you want to select articles or studies with the highest evidence level possible. If there are no studies available for the best evidence level, move down to the next appropriate level and search for evidence there.

Based on the type of clinical question you are trying to answer, the type of evidence you will need to look for changes.

THERAPYDetermining the effect of intervention

|

Look for:

|

DIAGNOSIS Identification of the nature of an illness or other problem by examining the symptoms

|

Look for:

|

PROGNOSISInformation on the course of a disease or condition over time, expected complications.

|

Look for:

|

ETIOLOGYCause(s) or manner of causation of a disease or condition

|

Look for:

|

PREVENTIONTo reduce the chance of disease by identifying the risk factors and modifying them.

|

Look for:

|

For more in depth information on the levels of evidence, please visit the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine website.

UNDERSTANDING STUDY TYPES

BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND EXPERT OPINIONS

Background knowledge and expert opinions represent the lowest level of evidence for informing evidence-based practice. This type of evidence may take the form of a book chapter, an editorial in a journal, or an entry in an expert-based resource like Up-To-Date. Because these resources are not the result of high-quality research, they are useful for learning more about a topic but not for applying to your practice as the evidence base.

Here are some examples of background knowledge and expert opinions:

Here are some examples of background knowledge and expert opinions:

CASE REPORTS AND CASE STUDIES

Case studies and case reports represent one of lower levels of evidence in the medical literature. These are typically detailed descriptions of an unusual manifestation of an illness or condition in a particular patient, including the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment.

Here are some examples of case studies and case reports:

Here are some examples of case studies and case reports:

CASE-CONTROL STUDIES

Case-control studies are a higher level of evidence than both case reports and expert opinions. They compare patients that have a disease or outcome to patients that do not have a disease or outcome by looking back through these patients histories to compare how frequently exposure to a risk factor of interest occurred in each group.

Here are some examples of case-control studies:

Here are some examples of case-control studies:

COHORT STUDIES

Cohort studies are often the highest level of evidence that can be found for both etiology and prognosis questions. In cohort studies, a large group of subjects without a disease are defined by a variable (like birth year, etc.). At set periods of time in the future, they are studied to see if they have developed a disease or condition of interest, and this helps to define a causal link between a risk factor and a disease. Unlike case-control studies which look backward in time after someone already has a disease, cohort studies follow a group of people forward in time to see if the disease develops.

Here are some examples of cohort studies:

Here are some examples of cohort studies:

RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are one of the highest levels of evidence because they can statistically prove that an intervention has an effect on an outcome. RCTs are studies that involve the random allocation of participants to two groups: one group that receives an intervention or treatment, and one group that receives standard care or a placebo. The clinician conducting the study is blinded to which participants will be assigned throughout the trial, so results are unbiased.

Here are some examples of randomized controlled trials:

Here are some examples of randomized controlled trials:

SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Forming the second highest level of evidence, systematic reviews are a comprehensive review of the existing medical literature meeting a set of eligibility criteria as it pertains to a pre-defined research question. What this means is that researchers create a systematic, reproducible search strategy to uncover all related articles. They then analyze all of the articles (usually randomized controlled studies) related to a clinical question and that meet the criteria for inclusion, and summarize the findings. The researchers then make recommendations for clinical practice based on the strength of the evidence they find.

Here are some examples of systematic reviews:

Here are some examples of systematic reviews:

- The JOINT model of nurse absenteeism and turnover: A systematic review

- Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review

- The Effectiveness of Cooling Packaging Care in Relieving Chemotherapy-Induced Skin Toxicity Reactions in Cancer Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review.

META-ANALYSES

A meta-analysis is a type of systematic review that combines through statistical analysis the data from multiple studies, and identifies a common treatment effect. This is considered the highest level of medical evidence, and is thus placed at the top of the pyramid.

Here are some examples of meta-analyses:

Here are some examples of meta-analyses:

- Comparison of the effi cacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials

- The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis

- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Pros and Cons of Consuming Liquids Preoperatively.

John hopkins nursing evidence-based practice tool: Evidence level and guide

The John Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model has a guide which covers the different levels of evidence and quality of studies. It can be downloaded here.

Step 9: Summarize the individual evidence

APPRAISING SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE

After scouring the databases for studies that represent the highest level of evidence for your clinical question, it is time to evaluate the articles you have found. It is not enough to just read the articles on your given topic. You need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each study before deciding whether to apply its recommendations to your clinical practice.

While reading any scientific study, these are the three question you will want to ask yourself:

- Are the results valid?

- What are the results?

- Are the results relevant to my clinical question?

HOW TO READ A RESEARCH ARTICLE

Reading a research paper requires a different skill set than reading a novel or a newspaper article.

Research papers are organized into distinct sections, and knowing which sections will provide you with the information you need to determine the results, relevancy, and validity will save you time and energy.

Below are some short, simple videos that explain the how to efficiently read scientific articles.

Research papers are organized into distinct sections, and knowing which sections will provide you with the information you need to determine the results, relevancy, and validity will save you time and energy.

Below are some short, simple videos that explain the how to efficiently read scientific articles.

|

|

|

ARTICLES ON READING AND UNDERSTANDING RESEARCH

- Hoe, J., & Hoare, Z. (2012). Understanding quantitative research: part 1. Nursing Standard, 27(15-17), 52-57. Available from: Researchgate

- Hoare, Z., & Hoe, J. (2013). Understanding quantitative research: part 2. Nursing Standard, 27(18), 48-55. Available from: http://journals.rcni.com/doi/pdfplus/10.7748/ns2013.01.27.18.48.c9488

- Coughlan, M., Cronin, P., & Ryan, F. (2007). Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 1: quantitative research. British Journal Of Nursing, 16(11), 658-663. Available from: http://www.healthmantra.com/ortho/literature-review1.pdf

BOOKS ON APPRAISING RESEARCH STUDIES

The library has access to several eBooks on evidence-based practice that have chapters on appraisal. To access these titles off-campus, please contact the librarian for login credentials.

- Dang, D., & Dearholt, S.(2018). Johns Hopkins Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines, Third Edition. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International. (See chapters 6 & 7) Available from: R2 Digital Library

- Cutcliffe, J., & Ward, M. (2014). Critiquing Nursing Research. Luton: Andrews UK. Available from: eBooks by EBSCO

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. (2004). A practical guide for health researchers. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/119703

John Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice tools: Research & Non-Research Evidence appraisal Tools

The John Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model provides two tools to assist in the appraisal of individual studies, one for research studies and one for non-research studies. You can download both of these tools here.

ARE THE RESULTS VALID?

Validity is a measure of how sound a research study is. Does the study do what the researchers claim it does? There are two types of validity that you should look at when appraising the validity of a study- internal and external.

- Internal validity is how well the design and methodology of the study prevented any other factors from influencing the results besides the intervention under study.

- External validity, on the other hand, is the degree to which the results can be applied to a wider population or other settings.

ARTICLES ON VALIDITY

Here are some articles that can further explain how to assess the internal and external validity of a research article.

- Greenslaugh, T. (1997). Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ, 315(7103), 305-308. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2127212/pdf/9274555.pdf

- Heale, R., Twycross, A. (2015). Validity and reliability in quantitative studies.

Evidence-Based Nursing, 18(3), 66-67. Available from: http://ebn.bmj.com/content/ebnurs/18/3/66.full.pdf - Russell CK, Gregory DM. (2003) Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence-Based Nursing, 6(2) 36-40. Available from: http://ebn.bmj.com/content/6/2/36

VIDEOS ON VALIDITY

Below are a number of videos that explain internal and external validity that may help with your understanding of these concepts.

|

|

|

WHAT ARE THE RESULTS?

There are two main questions you will want to considering when evaluating what the results of a study are:

1. What are the overall results?

and

2. How precise are the results?

When trying to determine the overall results, you should be looking for the "Results" or "Findings" section of the article. The results may be presented in numerical format. When looking at this section, try to determine if the results are clear to you. Did the authors find a difference between the control group and the experimental group? And if the authors did find a difference, how large was the confidence interval? A smaller confidence interval indicates a more precise result.

Below are a number of resources that can help you understand the statistical terminology you will encounter while reading research papers.

1. What are the overall results?

and

2. How precise are the results?

When trying to determine the overall results, you should be looking for the "Results" or "Findings" section of the article. The results may be presented in numerical format. When looking at this section, try to determine if the results are clear to you. Did the authors find a difference between the control group and the experimental group? And if the authors did find a difference, how large was the confidence interval? A smaller confidence interval indicates a more precise result.

Below are a number of resources that can help you understand the statistical terminology you will encounter while reading research papers.

UNDERSTANDING THE RESULTS VIDEOS

HYPOTHESIS TESTINGUNDERSTANDING RISKINTENTION TO TREAT |

CONFIDENCE INTERVALSNUMBER NEEDED TO TREATDIFFERENCES IN RESEARCH |

ARTICLES ON UNDERSTANDING STATISTICS IN NURSING RESEARCH STUDIES

Here are some journal articles that provide some guidance on understanding statistics in nursing research that will be helpful in your appraisal of the evidence:

- Giuliano, K., & Polanowicz, M. (2008). Interpretation and use of statistics in nursing research. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 19(2), 211-222. Available from: OVID

- Sheldon ,T. (2000).Statistics for evidence-based nursing. Evidence-Based Nursing 3(1), 4-6. Available f from: http://ebn.bmj.com/content/3/1/4

BOOKS ON STATISTICS IN NURSING RESEARCH

Here are several textbooks you can refer to if you'd like more in-depth information on statistics in research.

- Stommel, M., & Dontje, K. J. (2014). Statistics for Advanced Practice Nurses and Health Professionals. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. Available from: EBSCO e-Books

- Woloshin, S., Schwartz, L., & Welch, H.G. (2008). Know Your Chances: Understanding Health Statistics. Berkeley, CA:University of California Press. Available from: PubMed Health

ARE THE RESULTS RELEVANT TO MY CLINICAL QUESTION?

After you understand the results of the study, and have determined that the study is valid, you must then determine whether the results are relevant to your clinical question and your local population.

The questions you will want to ask yourself are*:

*Adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist

The questions you will want to ask yourself are*:

- Are patients in this study similar enough to the population you are hoping to apply this to?

- Have all the important clinical outcomes been considered in this study?

- Do the benefits found in this study outweigh the risks to patients?

*Adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist

CASP CRITICAL APPRAISAL CHECKLISTS

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme out of Oxford, UK has developed a number of easy-to-use checklists to promote the practice of evidence-based medicine by helping health care staff make sense of scientific literature. These are free to download and use under the Creative Commons License.

OTHER APPRAISAL RESOURCES

AJN'S CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE EVIDENCE SERIES

In 2010, the American Journal of Nursing published a series of articles on EBP. Three of these articles focused on the critical appraisal of nursing literature. Below are full-text links for this series.

Article references:

- Critical Appraisal of the Evidence: Part I

- Critical Appraisal of the Evidence: Part II

- Critical Appraisal of the Evidence: Part III

Article references:

- Fineout-Overholt, E., Melnyk, B., Stillwell, S., & Williamson, K. (2010). Evidence-based practice step by step. Critical appraisal of the evidence: part I: An introduction to gathering, evaluating, and recording the evidence. American Journal Of Nursing, 110(7), 47-52. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000383935.22721.9c

- Fineout-Overholt, E., Melnyk, B., Stillwell, S., & Williamson, K. (2010). Evidence-based practice, step by step. Critical appraisal of the evidence: Part II: Digging deeper--examining the 'keeper' studies. [corrected] [published erratum appears in AM J NURS 2010 Nov;110(11):12]. American Journal Of Nursing, 110(9), 41-48. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000388264.49427.f9

- Fineout-Overholt, E., Melnyk, B., Stillwell, S., & Williamson, K. (2010). Critical appraisal of the evidence: part III the process of synthesis: seeing similarities and differences across the body of evidence. American Journal Of Nursing, 110(11), 43-51.

CURRICULUM RENEWAL FOR EVIDENCE BASED MEDICINE

Below are a series of videos produced by Monash University and funded by the Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching which give a more in-depth look at appraising different types of medical studies.

APPRAISING STUDIES OF DIAGNOSIS |

APPRAISING STUDIES OF

|

APPRAISING STUDIES OF

|

APPRAISING STUDIES OF

|

|

|

|

APPRAISING STUDIES OF PROGNOSIS |

APPRAISING SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS |

Step 10: Synthesize overall strength and quality of evidence

JOHN HOPKINS NURSING EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE TOOLS: Individual Evidence Summary Tool

John Hopkins provides a tool to help you summarize the evidence from the articles you've collected, called the Individual Evidence Summary Tool. You can download it here.

Click to set custom HTML

Step 11: Develop recommendations for change based on evidence synthesis

JOHN HOPKINS NURSING EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE TOOLS: Evidence Synthesis and Recommendation Tool

John Hopkins provides an Evidence Synthesis and Recommendations Tool, which you can download here. This tool guides you through the process of making evidence-based recommendation from your findings in the literature.